Can Bitcoin's 10-minute block time truly replace the traditional calendar?

The US SEC approved spot Bitcoin ETFs at block 826,565. By block 840,000, these ETFs held over 800,000 Bitcoins. As of block 925,421—based on real-time data at that point—US spot Bitcoin ETFs collectively held about 5% to 6% of all circulating Bitcoin.

Without additional context, you might not immediately realize these blocks correspond to January 2024, April 2024, and November 27, 2025. Yet even without labels like “year” or “month,” the narrative remains clear—the critical factor is the chronological order of the blocks.

The Bitcoin system actually operates with two distinct concepts of time. According to developer documentation, the Bitcoin blockchain is fundamentally an ordered ledger where each block references its predecessor. Every 2,016 blocks, mining difficulty is recalculated to keep the average block interval near ten minutes.

Both Bitcoin halving events and network upgrades are triggered by “block height” (the block number), not by a specific calendar date. Block height is absolutely precise, while calendar dates must be estimated from hash rate, introducing uncertainty. Civil time for humans is measured in days and hours, but Bitcoin defines event order strictly by ever-increasing block height. In contrast, real-world timestamps can deviate within consensus limits, and short-term chain reorganizations can even temporarily change an event’s “time label.”

Bitcoin advocate and software engineer Der Gigi describes Bitcoin units as “stored time” and the Bitcoin network as a “decentralized clock.” Satoshi Nakamoto originally named the ledger “Timechain” in pre-release code, underscoring that its core design goal is not just data storage but chronological ordering of events.

Developers plan forks based on block height. While the mapping between block height and future calendar dates is imprecise—dependent on future hash rate and recalibrated only every 2,016 blocks—calendar date deviations remain acceptable until the next difficulty adjustment.

Describing ETF developments using six-digit block heights reveals an essential truth: marking history by block height is not a meme, but a crucial debate about which clock the Internet will ultimately trust.

Time Is Power: Whoever Controls the Clock Controls the Network

Before 1960, time standards were set by Earth’s rotation and national observatory data. Afterwards, major nations developed Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which became the global standard in the 1960s. UTC is a “political and technical compromise”—it’s based on International Atomic Time (TAI) with manually inserted leap seconds (scheduled for phase-out by 2035).

Controlling the time standard means controlling the foundational coordination infrastructure for finance, aviation, communications, and more.

In 1985, David Mills introduced the Network Time Protocol (NTP), enabling networked devices to synchronize UTC time to millisecond precision. NTP evolved into a self-organizing hierarchy of time servers, becoming the backbone of Internet time synchronization.

From the telegraph era onward, governments and standards bodies have held the privilege of controlling the clock—and thus, the network.

Satoshi Nakamoto bypassed this entire hierarchy. The Bitcoin whitepaper proposed a “peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server” to generate proof-of-work for transaction ordering. In Satoshi’s code, the ledger was called “Timechain,” highlighting that the primary design goal is chronological ordering of events, not simply transferring funds.

In his 1978 paper, Leslie Lamport argued that in distributed systems, the top priority is “consistent ordering of events,” not exact synchronization with real-world clocks. Bitcoin, at its core, is a “Lamport clock powered by energy consumption”—using Proof of Work (PoW) to guarantee total ordering and a roughly steady cadence, replacing reliance on trusted time servers with “energy plus consensus rules.”

The Nature of Block Time: Probabilistic Intervals, Not Real-World Clocks

Bitcoin block generation follows a Poisson process: while the average interval is ten minutes, actual block times follow an exponential distribution—intervals may be as short as a few seconds or as long as several dozen minutes.

In contrast, Bitcoin’s timestamp design is intentionally imprecise. Bitcoin engineer Pieter Wuille points out that the time field in a block header should be treated as a reference accurate only to the hour.

This deliberate imprecision is by design: Bitcoin only requires timestamps accurate to within one or two hours to meet difficulty adjustment and reorg rules.

So what is “network-adjusted time”?

- Node median calculation: Each node collects time reports from its peers and uses the median as its own “current time” adjustment baseline.

- Independent of NTP: This mechanism exists solely within the Bitcoin P2P network, with no reliance on external time servers.

- Validity window: A block’s timestamp is valid only if it’s ① greater than the median of the previous 11 blocks’ timestamps, and ② not more than two hours ahead of the node’s network-adjusted time.

- Key insight: The coarse granularity of timestamps (hours, not minutes) is intentional; block height is what ensures strict event ordering. Bitcoin Core specifies that as long as the timestamp exceeds the median of the prior 11 blocks and is within “network-adjusted time + 2 hours,” it’s valid.

For those interested in “human time,” timestamps are flexible. For those focused on “event order,” block height is absolutely precise. Bitcoin intentionally relaxes real-world clock precision because what truly matters is the event sequence guaranteed by Proof of Work and block height.

Recording History by Block: Blockchain as the Authoritative Time Standard

The Bitcoin community has long treated block height as the authoritative time marker. For example, BIP-113 redefined “locktime” to use the median of previous blocks’ times instead of wall-clock time, making the blockchain itself the core reference for time progression.

To determine when an event “actually happened” in Bitcoin, its only standard is its position on the blockchain.

Timestamp research already treats blockchains as neutral, append-only time anchors. Blockchain timestamping studies propose anchoring event hashes to a public chain to prove that as of block X, a document existed—essentially the historian’s practice of citing block height.

The art and media worlds are exploring this as well: Matt Kane’s Gazers project synchronizes its internal calendar with lunar cycles and on-chain triggers; Web3 archival projects describe themselves as “documents in blockchain time,” treating blockchain state as the authoritative reference for existence.

A 2023 economics paper argued that “Timechain” better captures Bitcoin’s essence than “blockchain,” framing the ledger as a time-ordering system. This is not just conceptual hype—it’s an acknowledgment of Bitcoin’s core value by economists.

Real-World Friction: Human Ritual Versus Probabilistic Blocks

Because timestamp rules are relaxed, block times can occasionally “move backward”: consensus requires only that the median time of the prior 11 blocks increases, not each individual block’s timestamp. This doesn’t affect security, but it does create confusion for historical records demanding sub-hour precision.

Short-term chain reorganizations can temporarily change an event’s timestamp—some protocol researchers have even titled papers, “In Bitcoin, Time Doesn’t Always Move Forward.”

The deeper issue is a gap in social perception: human life is organized around weeks, months, and ritualized calendars (holidays, anniversaries). UTC exists to map these rhythms to the clock. Bitcoin’s ten-minute “heartbeat” ignores weekends and holidays—a strength for a neutral system, but for most people, “block 1,234,567” is less intuitive than “January 3, 2029.”

Security note: Bitcoin has had “timewarp” vulnerabilities—miners could collude to manipulate timestamps and slow difficulty increases. While this is now tightly constrained, the community continues to discuss how consensus rules might fully resolve it. This is central to debates over Bitcoin’s reliability as a clock.

Beyond Bitcoin: The Lindy Effect and Schelling Point

A market commentary once said, “If Bitcoin is a clock written by God, Ethereum is a plant,” emphasizing Bitcoin’s fixed supply and hardcoded rhythm. As the oldest, most secure proof-of-work chain, Bitcoin’s accumulated energy investment far exceeds any other project, making it the only ideal neutral time standard.

Academic research shows that security and longevity are critical for any time standard—a clock not expected to last a century cannot be a reliable archival anchor.

Bitcoin’s Lindy effect (the longer it exists, the more likely it will continue) and mining-driven economics make it the default Schelling point for Internet time. Even if other public chains generate blocks faster, they cannot replace Bitcoin’s position. Ethereum’s flexibility makes it better suited as a programmable environment than a stable metronome.

Today, Android devices offer “Timechain” plugins displaying Bitcoin block height on the home screen. Physical Bitcoin calendars are also available. Most blockchain explorers show both block height and human timestamps, but usually highlight the latter. If this default were reversed, it could signal the mainstreaming of block time.

UTC’s global adoption took years of negotiation; in crypto, BIPs (Bitcoin Improvement Proposals) have become the practical standard for time interpretation rules.

It’s easy to imagine future industry norms: “Citations for on-chain events must include block height; calendar date is optional.”

Crypto media already describe halving events using block numbers—cultivating the habit of treating block height as the core time reference. Web3 archival projects suggest that museum exhibit labels may eventually display both block 1,234,567 and October 5, 2032.

A standard citation format could be: Bitcoin Mainnet #840,000 (hash: 00000000…83a5)—April 20, 2024 (UTC, Halving Event).

This format eliminates ambiguity and enables machine verification across forks and testnets.

Some papers propose anchoring hashes on public chains to prove a document existed no later than a specific block’s creation. Courts may one day accept such blockchain time anchors as evidence. In fact, Git already uses hashes to define the order of code changes, with real-world clocks as a secondary reference.

Bitcoin doesn’t need to replace UTC. Its more reasonable role is as a parallel timeline for digital history—verifiable and neutral, grounded in energy and consensus, and ideal for on-chain events and digital archives.

The real question is: How deeply will this timeline permeate law, archives, and collective memory?

2040: A World Where Block Height Comes First

A historian opens an archive entry and sees: “First spot Bitcoin ETF approved: block 826,565 (January 10, 2024)”—the calendar date appears in parentheses as a supplemental authoritative reference.

Her editor asks, “Do we need to keep the calendar date?” The historian deletes it—readers who need it can convert for themselves.

The wall clock reads 3:47 PM, while her phone’s Timechain plugin shows block 2,100,003. Both times are “correct”: the former is based on Earth’s rotation and political compromise, the latter on cumulative proof of work since the Genesis Block.

For her dissertation on the institutionalization of Bitcoin, the latter is what matters—a clock that can’t be tampered with, doesn’t observe daylight saving, and every tick traces back to the Genesis Block.

It’s not the only clock, but for a growing array of events, it’s the meaningful one.

Statement:

- This article is reprinted from [Foresight News], with copyright belonging to the original author [Gino Matos]. If you have any concerns about this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, who will address the matter promptly according to established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is cited, do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize this translated article.

Related Articles

In-depth Explanation of Yala: Building a Modular DeFi Yield Aggregator with $YU Stablecoin as a Medium

BTC and Projects in The BRC-20 Ecosystem

What Is a Cold Wallet?

Blockchain Profitability & Issuance - Does It Matter?

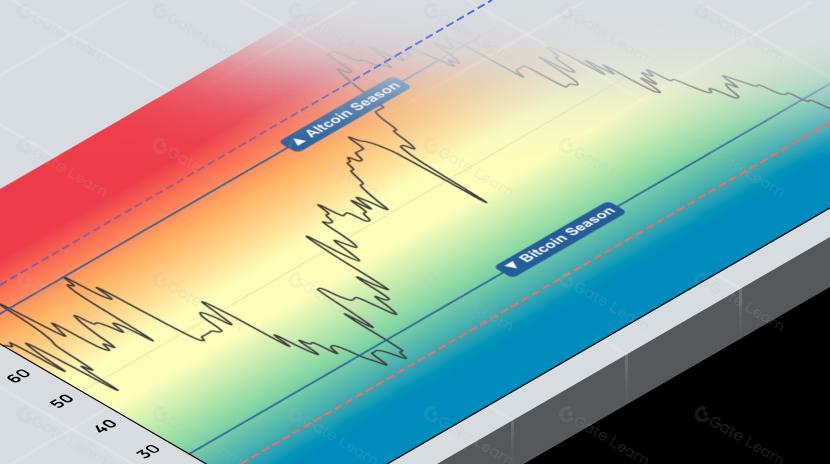

What is the Altcoin Season Index?