Specialized Stablecoin Fintechs

Over the last two decades, fintech has changed how people access financial products, but not how money actually moves. Innovation focused on cleaner interfaces, smoother onboarding, and better distribution, while the core financial infrastructure remained largely unchanged. For most of this period, the stack was being resold, but not rebuilt.

Broadly speaking, fintech’s evolution can be divided into four phases:

Fintech 1.0: Digital Distribution (2000–2010)

The earliest wave of fintech made financial services more accessible, but not meaningfully more efficient. Companies like PayPal, E*TRADE, and Mint digitized existing products by wrapping legacy systems—ACH, SWIFT, and card networks built decades earlier—with internet interfaces.

Settlement was slow, compliance was manual, and payments closed on rigid schedules. This era put finance online, but it didn’t allow money to move in fundamentally new ways. What changed was who could use financial products, not how those products actually worked.

Fintech 2.0: The Neobank Era (2010–2020)

The next unlock came from smartphones and social distribution. Chime targeted hourly workers with early access to paychecks. SoFi focused on refinancing student loans for upwardly mobile graduates. Revolut and Nubank reached underbanked consumers globally with consumer-friendly UX.

Each company told a sharper story to a specific audience, but they were all selling essentially the same product: checking accounts and debit cards running on the same legacy rails. They relied on sponsor banks, card networks, and ACH just as their predecessors had.

These companies didn’t win because they built new rails, but rather they reached customers better. Brand, onboarding, and customer acquisition were the advantages. Fintechs in this era became skilled distribution businesses layered on top of banks.

Fintech 3.0: Embedded Finance (2020 - 2024)

Around 2020, embedded finance took off. APIs made it possible for almost any software company to offer financial products. Marqeta let companies issue cards through an API. Synapse, Unit, and Treasury Prime offered banking as a service. Soon, nearly every app could offer payments, cards, or lending.

But beneath the abstraction, nothing fundamental changed. Banking-as-a-service (BaaS) providers still depended on the same sponsor banks, compliance frameworks, and payment rails of earlier eras. The abstraction moved one layer up from banks to APIs, but economics and control still flowed back to the legacy system.

The Commoditization of Fintech

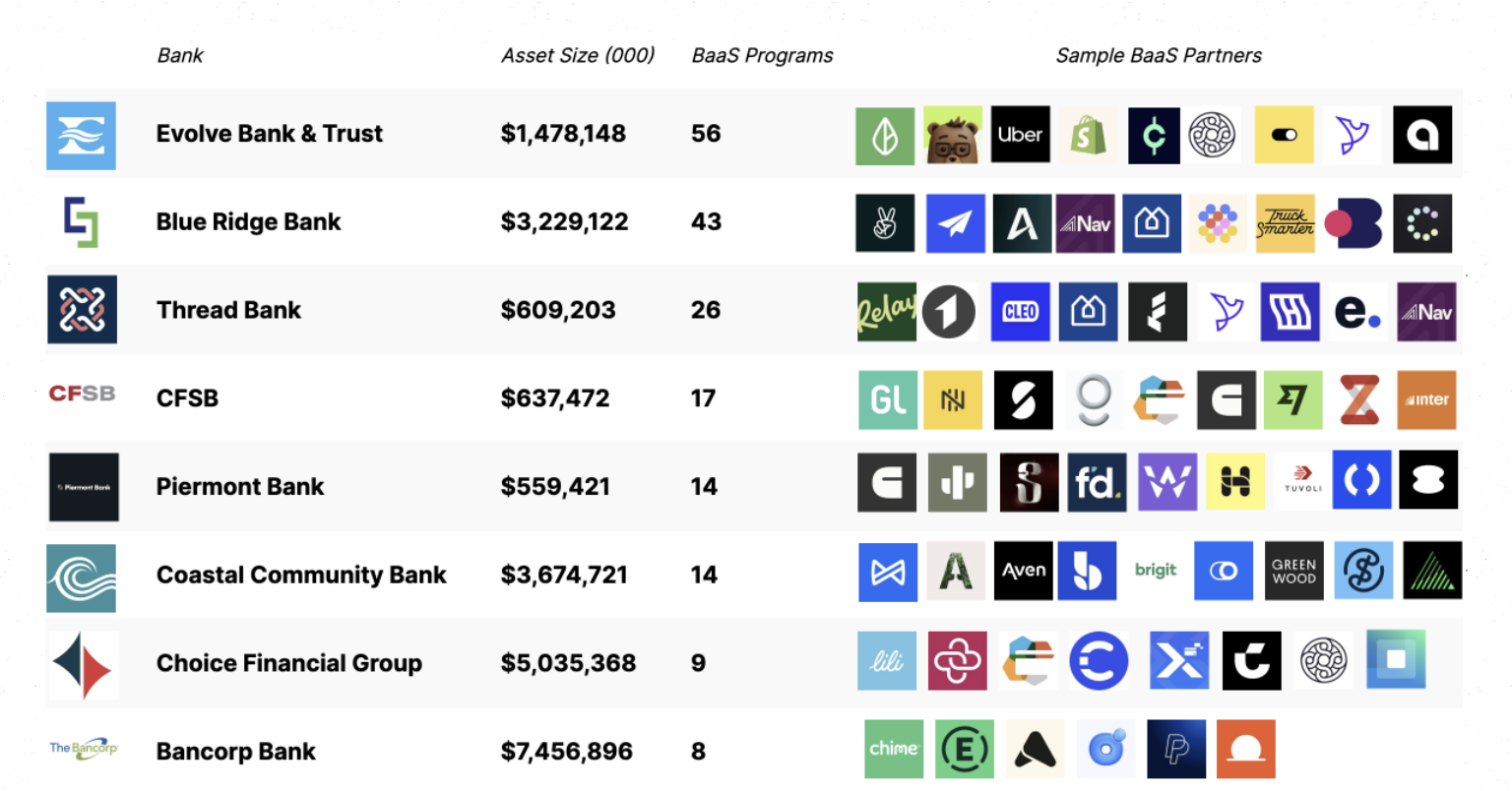

By the early 2020s, cracks in this model were everywhere. Nearly every major neobank relied on the same small set of sponsor banks and BaaS providers.

Source: Embedded

As a consequence, customer-acquisition costs soared as each company waged war against one another through performance marketing. Margins compressed, fraud and compliance costs ballooned, and infrastructure practically became indistinguishable. The competition turned into a marketing arms race. Card colors, signup bonuses, and cashback gimmicks are how many of the fintechs tried to differentiate.

At the same time, risk and value capture concentrated at the bank layer. Large institutions like JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, regulated by the OCC, retained core privileges: accepting deposits, making loans, and accessing federal payment rails like ACH and Fedwire. Fintechs such as Chime, Revolut, and Affirm lacked those privileges and depended on licensed banks to provide them. Banks earned interest margins and platform fees; fintechs earned interchange.

As fintech programs proliferated, regulators increasingly scrutinized the sponsor banks that sat underneath them. Consent orders and heightened supervisory expectations forced banks to invest heavily in compliance, risk management, and oversight of third-party programs. For example, Cross River Bank entered into a consent order with the FDIC, Green Dot Bank was subject to an enforcement action from the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Reserve issued a cease-and-desist order against Evolve.

Banks responded by tightening onboarding, limiting the number of programs they would support, and slowing product iteration. What once allowed experimentation increasingly required scale to justify the compliance burden. Fintech grew slower, more expensive, and biased toward broad, general-purpose products rather than specialized ones.

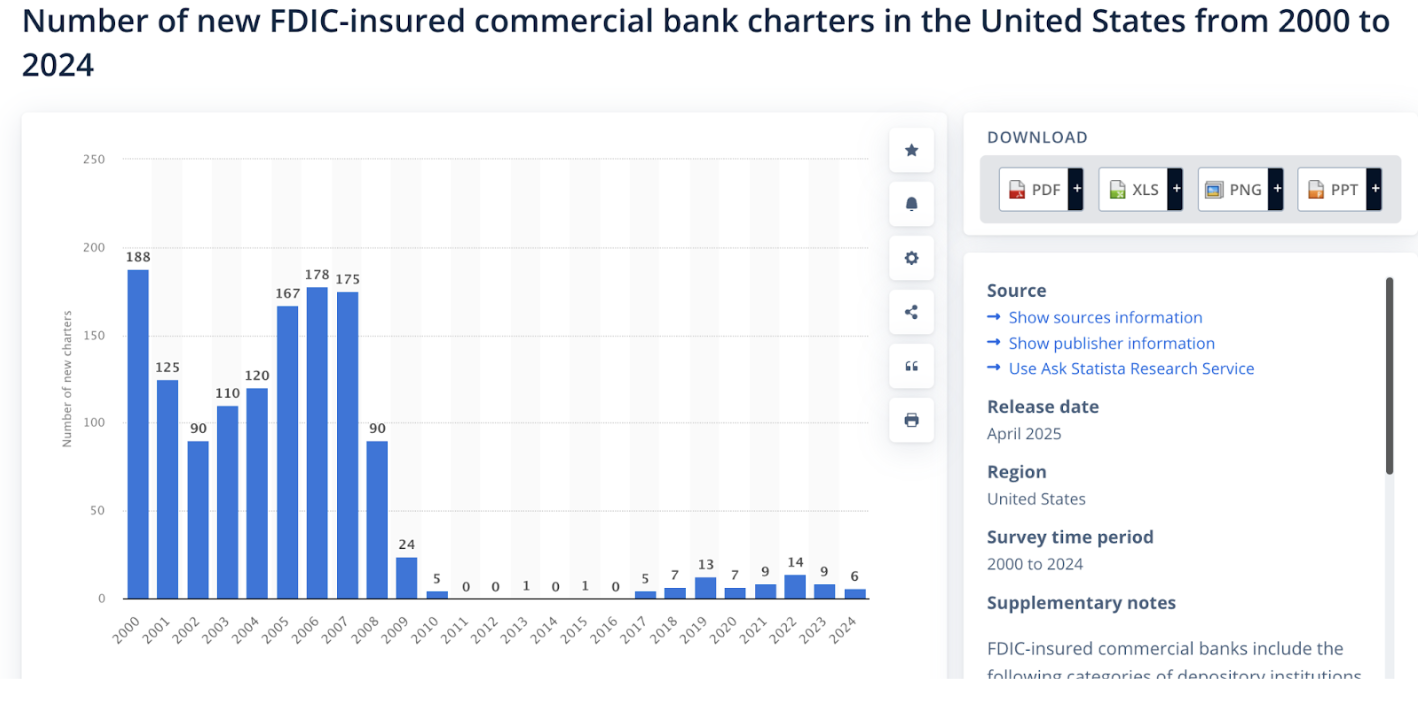

In our view, there are three main reasons innovation stayed at the top of the stack over the last 20 years.

- Money movement infrastructure was monopolized and closed. Visa, Mastercard, and the Fed’s ACH network leave no room for competition.

- Startups needed a lot of capital to create finance-first products. Launching a regulated banking app requires millions of dollars for compliance, fraud prevention, treasury operations, and so forth.

- Regulation limited direct participation. Only chartered institutions could custody funds or move money over core rails.

Source: Statista

Given those constraints, it made far more sense to build products than to fight the rails themselves. The result is that most fintechs are polished wrappers around bank APIs. Despite two decades of innovation, the industry produced few genuinely new financial primitives. For a long time, there was no practical alternative.

Crypto followed the opposite trajectory. Builders focused on primitives first. Automated market makers, bonding curves, perpetual contracts, liquidity vaults, and on-chain credit emerged from the ground up. For the first time, financial logic itself became programmable.

Fintech 4.0: Stablecoins and Permissionless Finance

Despite all the innovation in the first three fintech eras, the plumbing underneath barely changed. Whether products were delivered through banks, neobanks, or embedded APIs, money still moved on closed, permissioned rails controlled by intermediaries.

Stablecoins break that pattern. Instead of layering software on top of banks, stablecoin-native systems replace key banking functions directly. Builders interact with open, programmable networks. Payments settle on-chain. Custody, lending, and compliance shift from contractual relationships to software.

BaaS reduced friction, but it didn’t change the economics. Fintechs still paid rent to sponsor banks for compliance, to card networks for settlement, and to intermediaries for access. Infrastructure remained expensive and permissioned.

Stablecoins remove the need to rent access at all. Instead of calling bank APIs, builders write to open networks. Settlement happens directly on-chain. Fees accrue to protocols rather than intermediaries. And we believe the cost floor falls dramatically, from millions of dollars to build through banks, or hundreds of thousands via BaaS, to thousands with smart contracts on permissionless chains.

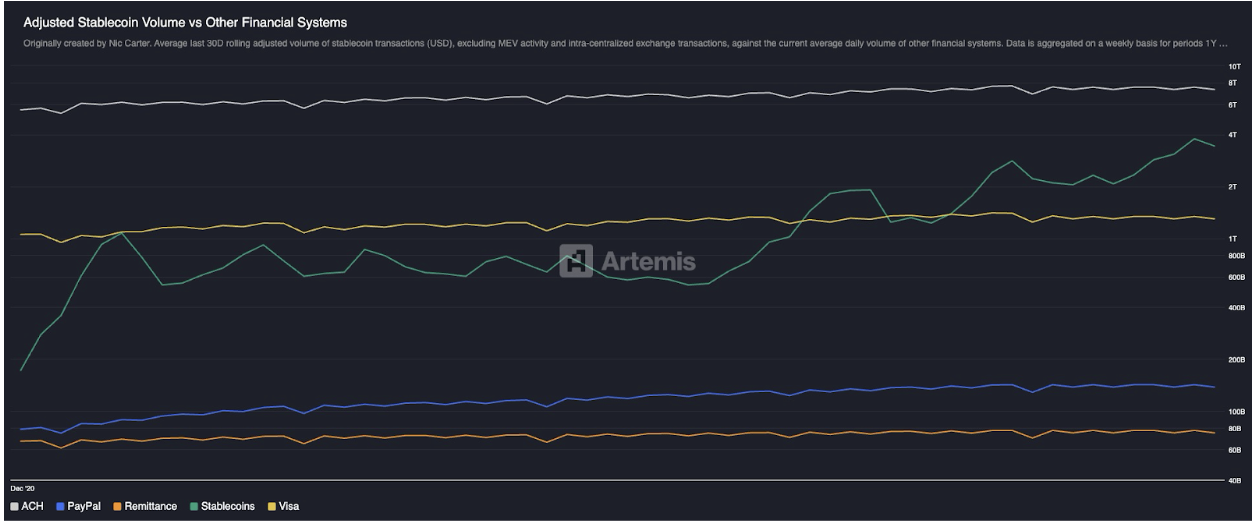

That shift is already visible at scale. Stablecoins have grown from nearly zero to roughly $300 billion in market cap in under a decade and now process more real economic volume than traditional payment networks like Paypal and Visa, even after excluding intra-exchange transfers and MEV. For the first time, non-bank, non-card rails operate at true global scale.

Source: Artemis

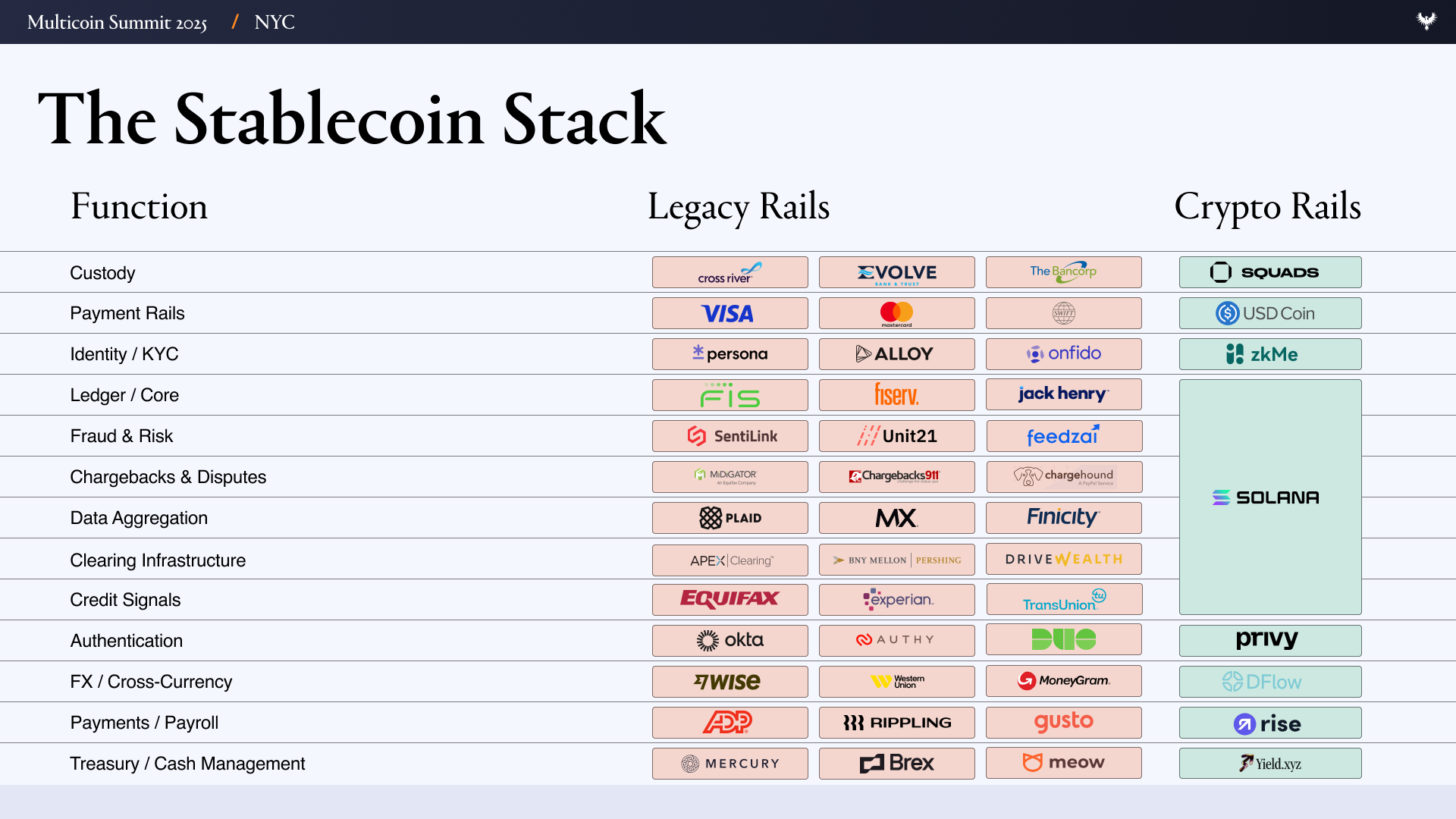

To understand why this shift matters in practice, it helps to look at how fintechs are built today. The typical fintech relies on a massive stack of vendors:

- User interface / UX

- Banking/custody layer - Evolve, Cross River, Synapse, Treasury Prime

- Payment rails - ACH, Wire, SWIFT, Visa, Mastercard

- Identity and compliance - Ally, Persona, Sardine

- Fraud Prevention - SentiLink, Socure, Feedzai

- Underwriting / Credit infra - Plaid, Argyle, Pinwheel

- Risk & Treasury infra - Alloy, Unit21

- Capital markets - Prime Trust, DriveWealth

- Data aggregation - Plaid, MX

- Compliance/reporting - FinCEN, OFAC checks

Launching a fintech on this stack means managing contracts, audits, incentives, and failure modes across dozens of counterparties. Every layer adds cost and delay, and many teams spend as much time coordinating infrastructure as they do building product.

Stablecoin-native systems collapse this complexity. Functions that once spanned half a dozen vendors converge into a small set of on-chain primitives.

In a stablecoin and permissionless finance world, banking and custody gets replaced by Altitude. Payment rails get replaced by stablecoins. Identity and compliance is needed but we believe it can live on-chain and can remain confidential and secure through things like zkMe. Underwriting and credit infra is overhauled and moves on chain. Capital markets companies become irrelevant when all assets become tokenized. Data aggregation gets replaced by on-chain data and selective transparency using things like fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). Compliance and OFAC get handled at the wallet layer (e.g., Alice can’t interact with a protocol if her wallet is on a sanctions list).

This is the real difference with Fintech 4.0: the plumbing of finance is finally changing. Instead of building another app that quietly begs banks for permission in the background, people are just replacing whole chunks of what banks do with stablecoins and open rails. Builders aren’t tenants anymore; they own the land.

The Opportunity For Specialized Stablecoin Fintechs

The first-order effect of this transition is simple: there can be far more fintechs. When custody, lending, and money transfer become nearly free and instant, launching a fintech company starts to look like launching a SaaS product. In a stablecoin-native world, there are no sponsor-bank integrations, card-issuer intermediaries, multi-day clearing windows, or redundant KYC checks to slow you down.

We believe that the fixed cost of launching a finance first fintech product also collapses from millions to thousands. Once infrastructure, customer acquisition costs (CAC), and compliance barriers vanish, startups will begin to profitably serve smaller, more specific segments of society through what we’re calling specialized stablecoin fintechs.

There’s a clear historical parallel here. The previous generation of fintechs began by serving distinct customer segments: SoFi with student-loan refinancing, Chime with early paycheck access, Greenlight with debit cards for teens, and Brex with founders who couldn’t obtain traditional business credit. But specialization failed as a durable operating model. Interchange capped revenue, compliance costs scaled. Sponsor-bank dependencies required expansion beyond the original niche. To survive, teams were pushed to expand horizontally, eventually adding products not because users demanded them, but because the infrastructure required scale to be viable.

Because crypto rails and permissionless finance APIs drastically reduce launch costs, a new wave of stablecoin neobanks will emerge, each targeting specific demographics, much like fintech’s early innovators. With dramatically lower overhead, these neobanks can focus on narrower, more specialized markets and stay specialized: Sharia-compliant finance, crypto degen lifestyles, or athletes with unique earning and spending patterns.

The second-order effect is even more powerful: specialization improves unit economics. CAC falls, cross-selling becomes easier, and per-customer LTV grows. Specialized Fintechs can align product and marketing precisely with niche cohorts that convert efficiently, and get more word of mouth by serving specific population segments. These businesses spend less on overhead yet have a clearer path to earning more per customer than the previous generation of fintechs.

When anyone can launch a fintech in weeks, the question shifts from “who can reach the customer?” to “who truly understands them?”

Exploring The Design Space for Specialized Fintechs

The most compelling opportunities emerge where legacy rails break down.

Take adult creators and performers, for example. They generate billions in income annually but are routinely deplatformed by banks and card processors because of reputational and chargeback risk. Payouts are delayed by days, withheld for “compliance review,” and often carry 10–20% fees through high-risk payment gateways, such as Epoch, CCBill, and others. We believe stablecoin-based payments could offer instant, irreversible settlement with programmable compliance, allowing performers to self-custody their earnings, route income to tax or savings wallets automatically, and receive payment globally without relying on high-risk intermediaries.

Now consider professional athletes, particularly in solo sports like golf and tennis, who face unique cash-flow and risk dynamics. Their income is concentrated into short career windows, often split among agents, coaches, and staff. They pay taxes across multiple states and countries, and risk injury disrupting earnings entirely. A stablecoin-native fintech could help them tokenize future income, use multi-sig wallets for staff payments, and automate tax withholding by jurisdiction.

Luxury goods and watch dealers are another example of a market poorly served by legacy financial infrastructure. These businesses routinely move high-value inventory across borders, often transacting six-figure sums via wires or high-risk payment processors, while waiting days for settlement. Working capital is frequently tied up in inventory sitting in safes or display cases rather than bank accounts, making short-term financing both expensive and difficult to access. We believe a stablecoin-native fintech can address these constraints directly: instant settlement for large transactions, credit lines collateralized by tokenized inventory, and programmable escrow built into smart contracts.

Once you look at enough of these cases, the same constraint shows up again and again: banks aren’t set up to serve users with global, uneven, or unconventional cash flows. But these groups can become profitable markets on stablecoin rails, and some examples of theoretical specialized stablecoin fintechs we find compelling include:

- Professional athletes: earnings are concentrated in a short time period; travel and relocate often; may have to file taxes in many jurisdictions; have coaches, agents, trainers, etc. on the payroll; may want to hedge injury risk.

- Adult performers and creators: excluded by banks and card processors; audience spread across the world.

- Employees at unicorns: cash “poor” with net worth concentrated in illiquid equity; may face expensive taxes on option exercise.

- On-chain builders: net worth concentrated in highly volatile tokens; pains around off-ramping and taxes.

- Digital nomads: passportless bank with auto FX swaps; tax automation depending on location; frequent travel/relocation.

- Prisoners: it is difficult and expensive for family/friends to get value into the prison system; money often doesn’t show up via traditional providers.

- Sharia compliant: avoidance of interest.

- Gen Z: credit-lite banking; investing through gamification; social features.

- Cross-border SMEs: expensive FX; slow settlement; frozen working capital

- Degens: pay to spin the roulette wheel against your credit card bill.

- Foreign aid: aid flows are slow, intermediated, and opaque; there’s a lot of leakage through fees, corruption, and misallocation

- Tandas / rotating savings clubs: cross-border by default for families that are global; pooled savings earn yield; potentially can build income history on chain for credit

- Luxury goods dealers (e.g., watch dealers): working capital tied up in inventory; require short term loans; conduct many high value, cross-border transactions; often transact through chat apps like WhatsApp and Telegram.

Summary

For most of the past two decades, fintech innovation focused on distribution, not infrastructure. Companies competed on branding, onboarding, and paid acquisition, but the money itself still moved over the same closed rails. That expanded access, but it also led to commoditization, rising costs, and thin margins that were hard to escape.

Stablecoins promise to change the economics of building financial products. By turning things like custody, settlement, credit, and compliance into open, programmable software, they materially lower the fixed cost of launching and operating a fintech. Capabilities that once required sponsor banks, card networks, and sprawling vendor stacks can now be built directly on-chain, with far less overhead.

When infrastructure gets cheaper, specialization becomes possible. Fintechs no longer need millions of users to make the math work. They can instead focus on narrow, well-defined communities whose needs are poorly served by one-size-fits-all products. Groups like athletes, adult creators, K-pop fans, or luxury watch dealers already share context, trust, and behavior, making it easier for products to spread organically rather than through paid marketing.

Just as important, these communities tend to have similar cash-flow profiles, risks, and financial decisions. That consistency lets products be designed around how people actually earn, spend, and manage money, instead of abstract demographic categories. Word of mouth works not just because users know each other, but because the product genuinely fits the way the group operates.

If our vision becomes reality, the economic shift is meaningful. CAC falls as distribution becomes native to the community, while margins expand as intermediaries fall out of the stack. Markets that once looked too small or uneconomic become durable, profitable businesses.

In this world, fintech’s advantage moves away from brute-force scale and marketing spend and toward real contextual understanding. The next generation of fintech won’t win by trying to serve everyone. It will win by serving someone extremely well, on infrastructure built for how money actually moves.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [multicoin]. All copyrights belong to the original author [Spencer Applebaum & Eli Qian]. If there are objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and they will handle it promptly.

- Liability Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute any investment advice.

- Translations of the article into other languages are done by the Gate Learn team. Unless mentioned, copying, distributing, or plagiarizing the translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

In-depth Explanation of Yala: Building a Modular DeFi Yield Aggregator with $YU Stablecoin as a Medium

What is Stablecoin?

Stripe’s $1.1 Billion Acquisition of Bridge.xyz: The Strategic Reasoning Behind the Industry’s Biggest Deal.

Top 15 Stablecoins

A Complete Overview of Stablecoin Yield Strategies